It’s not every boy that gets to dream big and make those dreams become a reality by dint of a good friendship with an idol from their formative years… but Jeffrey Jacob Abrams has had just that kind of luck, though he also earned his cinematic credentials—and strengthened that special friendship— by paying his dues. Along with journeyman work as both a composer and screenwriter, J.J. Abrams exhibited a true love for the craft of filmmaking and the art of telling a good story… much like his boyhood idol.

It’s not every boy that gets to dream big and make those dreams become a reality by dint of a good friendship with an idol from their formative years… but Jeffrey Jacob Abrams has had just that kind of luck, though he also earned his cinematic credentials—and strengthened that special friendship— by paying his dues. Along with journeyman work as both a composer and screenwriter, J.J. Abrams exhibited a true love for the craft of filmmaking and the art of telling a good story… much like his boyhood idol.

Steven Spielberg’s early career set out a kind of road map for Abrams to follow… Starting out using consumer home movie cameras in an attempt to learn the basics of cinematic storytelling, both future directors spent their teenage years figuring out the craft from books and magazines. Maybe they might come across the occasional TV interview with an industry professional, or perhaps get real lucky with a visit to the inner-workings of the Hollywood dream factory itself… but mostly, their real classroom was a darkened movie theater showing them the potential of the medium they’d begun to explore. These kids were unabashed movie geeks who parsed each film they viewed as a kind of how-to manual, reverse-engineering them the way a talented home chef might recreate a fine dining meal in order to crack the secrets of what made it so special, so memorable, in the first place.

with an industry professional, or perhaps get real lucky with a visit to the inner-workings of the Hollywood dream factory itself… but mostly, their real classroom was a darkened movie theater showing them the potential of the medium they’d begun to explore. These kids were unabashed movie geeks who parsed each film they viewed as a kind of how-to manual, reverse-engineering them the way a talented home chef might recreate a fine dining meal in order to crack the secrets of what made it so special, so memorable, in the first place.

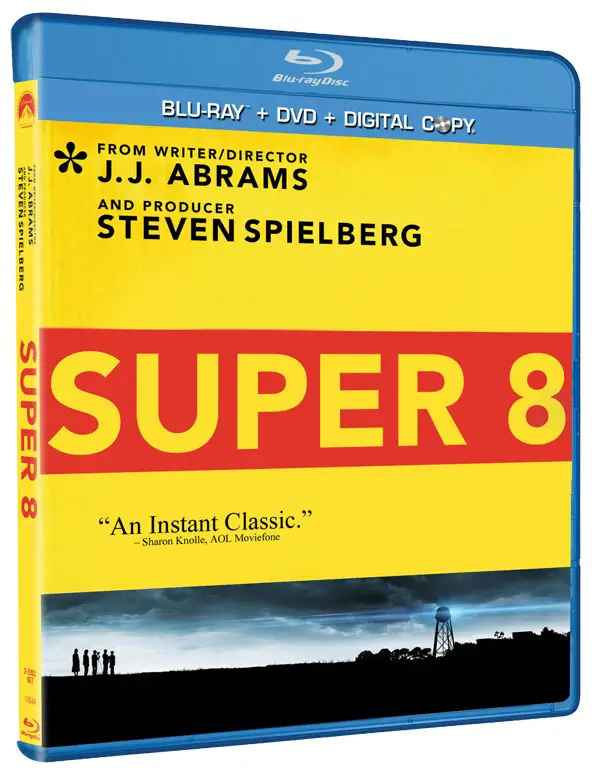

Growing to young men, eager to work in the entertainment industry, they followed much the same path in learning their craft: both moved on to television (Spielberg as a journeyman director on a variety of network dramas, while Abrams went one step further in moving up the screenwriting ladder to actually creating his own shows and producing them for broadcast networks) before finally taking the plunge into feature filmmaking. Though their stories are hardly identical, and diverge considerably at points in their respective careers, they aligned closely enough at one point for the teenage Abrams to have actually worked for Spielberg indirectly (cleaning up the older director’s youthful 8mm films with friend, Matt Reeves, who would also become a director of note). Decades later, they have formed a kind of mutual appreciation society that led directly to Spielberg producing Abram’s first personal feature film: Super 8.

Like Spielberg’s later career, Abrams project choices are rather eclectic, though action-oriented fare seems to be his comfort zone, and he seems to enjoy dealing with fantasy and science-fiction elements. In television he has created or assisted in the creation of espionage thrillers and dramas with strong science-fiction elements. In theatrical features he has followed much the same pattern during his brief directorial career (having already had an extensive screenwriting career for the big screen). He was brought onto Mission: Impossible III as a gun-for-hire based largely on his T.V. action cred and extensive screenwriting experience (with writing partners, Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci) and virtually drafted by Paramount to helm the reboot of Star Trek once his co-writing duties with Kurtzman and Orci were complete (he’d already signed on as the film’s producer). From there he produced, and had a huge co-writer/directorial impact upon, Cloverfield, which was based on an idea he thought up while on a shopping excursion with his son in a Japanese toy store.

Like Spielberg’s later career, Abrams project choices are rather eclectic, though action-oriented fare seems to be his comfort zone, and he seems to enjoy dealing with fantasy and science-fiction elements. In television he has created or assisted in the creation of espionage thrillers and dramas with strong science-fiction elements. In theatrical features he has followed much the same pattern during his brief directorial career (having already had an extensive screenwriting career for the big screen). He was brought onto Mission: Impossible III as a gun-for-hire based largely on his T.V. action cred and extensive screenwriting experience (with writing partners, Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci) and virtually drafted by Paramount to helm the reboot of Star Trek once his co-writing duties with Kurtzman and Orci were complete (he’d already signed on as the film’s producer). From there he produced, and had a huge co-writer/directorial impact upon, Cloverfield, which was based on an idea he thought up while on a shopping excursion with his son in a Japanese toy store.

Nevertheless, aside from his hit T.V. shows, it might be said that Abrams hasn’t really made a substantial impact on filmmaking or mere popcorn entertainment with perhaps the exception of Star Trek, which did in fact successfully reboot the franchise and has fans eagerly awaiting his next directorial effort in Roddenberry’s progressive final frontier. Cloverfield, directed by Matt Reeves was fun, and MI:III was typical of the series (though perhaps a bit better in regards to its action quotient) but ultimately, Abrams has not yet built up a strong track record for the kind of rich personal projects and massive entertainment events that Spielberg will long be remembered for… and with Super 8 he aimed to change that.

Directors sometimes shine the light on other filmmakers who’ve inspired them by creating various homages to films that helped them craft their own techniques and style over time. Sometimes it is but a small flourish in a scene or sequence, perhaps to make a point or simply to offer a nod to past masterpieces, or even to shake the viewer’s memory so that there is a connection and foundation for commentary within, or comparison to, the director’s own vision. Sometimes the homage is so great that the entire film is simply a director’s indulgence (or complete misfire), but full-blown homages don’t often work in cinema, for the comparison to a great, singular work is often tough to beat in the court of public opinion. On one hand you might end up with something akin to William Friedkin’s interesting Sorcerer (a nearly identical remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s incredible Wages of Fear) or come off for the worse with something like Gus Van Sant’s misfire Psycho (itself a literal scene-for-scene remake that’s more stunt than actual entertainment). Usually, for the most part, we’re exposed only to the grace notes… a quick wink by directors of skill to films of the past, or a loving consideration of old genres and styles that filmmakers like the Coen Bros. might elevate and enhance by way of their own unique vision.

It’s worth keeping all this in mind when watching Super 8 because an outright, full-blown homage to Spielberg’s career, most pointedly toward his “backyard adventures*,” is exactly what Abrams has set out to do. Whether you can appreciate his ambition in doing this, or simply watch the movie on its own merits as an exciting, boy’s life adventure, will either depend on your age, or how well-versed you are in pop-culture/cinematic history. Regardless, the powerful presence of Spielberg hangs over every frame of Abrams’ endeavor. Adults with any semblance of a good memory will be hard pressed to avoid seeing Super 8 without some kind of prejudice, and will probably end up comparing it to the essence of Spielberg films in the mid/late 70s and early 80s. For the younger set, unless their parents exposed them to those earlier works (and many have), the effect will be diluted and probably have no impact on viewing Super 8 as a fun, summertime popcorn flick with its heart in the right place.

That Spielbergian essence—the sense of displacement from family (almost always rocky or alienated due to change or loss), the sense of place and security within structured environments where the rules are suddenly upended dramatically, the sense of awe and wonder (or awe and fear) that comes with confronting an unknown elementseemingly outside of basic human truths and understanding, the sense of heroic purpose to confront the element and either defeat it or gain a greater appreciation of it, and the strong sense of sentimentality with regards to denouements where the family unit is strengthened or a childhood lost is regained—is what Abrams attempts to capture in his small-town, late-70s era tableau, where imaginative children are misunderstood but well-versed in emotional loss and the complexities of human relationships while the adults are but tragic ciphers, sinister authority figures or simply mere obstacles that stand in the way of achieving goals both practical and fantastic.

Within this ersatz setting, where the typical earth-toned decor and questionable clothing fashions are revealed to be not much more than a convenient place for Abrams to exercise his memory of how a Spielberg film should work,  a group of young teen children (played with by a fine cast of pros and newcomers) get together to work on a summer project. They’re filming a Super-8 horror movie that they’ll be able to enter into competition where the older kids hold sway. They think they have a good chance for success however, because their filmed zombie murders have finally been fleshed out with a decent story with character development (courtesy of the brightest, most faithful filmmakers of the bunch) and a new “wife” character to bounce dialogue off of… best of all, that key role will be played by their school’s own femme mystérieuse… a girl, whose father is from the wrong side of the steel mill. She holds the boys in the kind of awe reserved for cute little aliens that want to go home… but wait! there is an alien, and its not exactly cute, and frankly scares the bejesus out of the kids and the town proper. It’s hungry, telekinetic and very much just wants to put his ship together and go home… at least get away from the humans—military-types of the asshole variety—who wish to research him and probably do mean, nasty things rather than say, seek an understanding among species. The kids discover this beast by accident, virtually in their own backyard… While filming a setup involving a train station (it’s a meta moment in a

a group of young teen children (played with by a fine cast of pros and newcomers) get together to work on a summer project. They’re filming a Super-8 horror movie that they’ll be able to enter into competition where the older kids hold sway. They think they have a good chance for success however, because their filmed zombie murders have finally been fleshed out with a decent story with character development (courtesy of the brightest, most faithful filmmakers of the bunch) and a new “wife” character to bounce dialogue off of… best of all, that key role will be played by their school’s own femme mystérieuse… a girl, whose father is from the wrong side of the steel mill. She holds the boys in the kind of awe reserved for cute little aliens that want to go home… but wait! there is an alien, and its not exactly cute, and frankly scares the bejesus out of the kids and the town proper. It’s hungry, telekinetic and very much just wants to put his ship together and go home… at least get away from the humans—military-types of the asshole variety—who wish to research him and probably do mean, nasty things rather than say, seek an understanding among species. The kids discover this beast by accident, virtually in their own backyard… While filming a setup involving a train station (it’s a meta moment in a  movie designed for such things), a real train crash occurs and sets the action in motion… for within that banged up freight car is a military secret (okay, it’s the alien beast, not much of a secret).

movie designed for such things), a real train crash occurs and sets the action in motion… for within that banged up freight car is a military secret (okay, it’s the alien beast, not much of a secret).

I noted the kids were played by a fine cast… and they are. Casting directors, April Webster and Alyssa Weisberg should be commended, but Abrams directs them well and they maintain a youthful spontaneity, hitting their lines with flair and confidence for the most part. Young professional, Elle Fanning (the “sister of Dakota,” who now no longer needs that tag since taking on some accomplished roles of late), does a superb job as Alice Dainard, the lone girl in the boy’s club… Her acting chops ought to be a given, and they are exceptional. Her performance is finely nuanced and she has some fun within the role while ably expressing the sorrow of living with a broken-down father.

The secondary boys are played Zach Mills, Gabriel Basso and Ryan Lee (who gets the comic relief role of a little firebug just right), but it’s the the two main boys, newcomers Joel Courtney and Riley Griffiths (playing Joe Lamb and Charles Kaznyk respectively), that are standout performances in what would otherwise be special-effects driven popcorn fare. They do a great job of anchoring the film together and create a real bond, even though it’s mostly young Courtney’s show and he’s expected to carry the emotional weight of the film. In this particular kid, the filmmakers found a young actor of real promise.

While Griffiths as the pudgy, excitable, slightly megalomaniacal director, does an able job of parodying a youngOrson Wells first discovering the fabled train set of filmmaking tools, it’s mostly a one-note role save for a bit of romantic jealousy he’s tasked to display during one crucial scene. Joe Lamb, albeit a more complex character, is given a greater believability and depth in Joel Courtney’s fresh face and pleasantly mellow, likable demeanor. That face, when it’s asked by the director to hold the sadness of loss and memory, does an extraordinary job of grounding this fantasy/science-fiction film in reality… and the boy does a great job of holding his own against actors like Kyle Chandler (playing his father, Jack Lamb) or Ron

While Griffiths as the pudgy, excitable, slightly megalomaniacal director, does an able job of parodying a youngOrson Wells first discovering the fabled train set of filmmaking tools, it’s mostly a one-note role save for a bit of romantic jealousy he’s tasked to display during one crucial scene. Joe Lamb, albeit a more complex character, is given a greater believability and depth in Joel Courtney’s fresh face and pleasantly mellow, likable demeanor. That face, when it’s asked by the director to hold the sadness of loss and memory, does an extraordinary job of grounding this fantasy/science-fiction film in reality… and the boy does a great job of holding his own against actors like Kyle Chandler (playing his father, Jack Lamb) or Ron  Eldard (as the broken father figure, Louis Dainard). It’s not a showy role, hardly the thing that makes a career, but Courtney proves he has real acting ability throughout the film… he’s the complete opposite of the kind of annoying non-actor filmmaker’s might typically find for this kind of role. To put it simply, Joel Courtney is no Ke Huy Quan, and that’s a good thing (he’s more the Henry Thomas-type)… there’s an irresistible naturalness to him that easily draws you in and makes Joe Lamb a sympathetic character to root for.

Eldard (as the broken father figure, Louis Dainard). It’s not a showy role, hardly the thing that makes a career, but Courtney proves he has real acting ability throughout the film… he’s the complete opposite of the kind of annoying non-actor filmmaker’s might typically find for this kind of role. To put it simply, Joel Courtney is no Ke Huy Quan, and that’s a good thing (he’s more the Henry Thomas-type)… there’s an irresistible naturalness to him that easily draws you in and makes Joe Lamb a sympathetic character to root for.

The film opens with a nice, elegiac shot that’s all showing in order to tell rather than telling in order to show, a real indication that Abrams has studied his idol’s films well and beyond the surface… So many directors fail at this kind of expository background, and it’s nice to see Abrams handle it with simple elegance in order to move the story forward and give us all we need to know about the loss both Joe and his dad are struggling through. That simple shot is then reinforced by a deft sequence introducing the kids, who are pattering on about the tragedy and introduce the basic story elements. Joe still hangs on to his mother’s memory, always grasping a locket his mother gave him (a nice Spielbergian touch that doesn’t get overused, and serves to comment on Joe’s state of mind), while his father seems ready to let go of her memory in order to move on. Yet Joe’s father cannot get over the fact that her death would never have occurred had drunken Louis Dainard done his job, and refuses to let go of a grudge that eventually affects his son’s sense of self and personal growth. Leave it to the kids to wrestle with the sins of the fathers on their own terms as Joe finds out Charles “hired” Alice Dainard to be in his film in order to expand the story line (because there’s only so far you can take neato zombie kills, as any director will tell you). Shocked, because he harbors a crush on her and finds her a bit unattainable, Joe is able to put aside his feelings about what her dad did (at first so she’ll put aside her own prejudices toward him and save Charles’s shooting schedule) and accepts Alice for who she is, which in turn she’s willing to accept and reciprocate. However, the respective fathers stand in the way of their burgeoning understanding and blossoming romance.

In any other small town film this relationship would end badly (just like in any other film Elliot’s disintegrating family would fall further askew if not for the appearance of a certain cuddly extraterrestrial)… but as the kids soon discover, things are going to change really quick due to an unexpected event that is really just a monstrous metaphor for the tensions these folks feel toward one another… making them paranoid, unsettled, irrational. It’s the kind of big, unexpected event that eventually destroys all you love, or brings you closer to the ones you love… the kind of theme Spielberg has so often employed in his films and that Abrams simply can’t help dabbling in himself. Yet, in Abrams’ hands it all feels less organic, much more the kind of thing other Stevenistas have taken stabs at and failed with (e.g. the debut of Phil Joanou, one of Spielberg’s early proteges).

That’s the crux of any criticism I can give this generally well-acted, nicely-crafted work… it lacks any sense that it’s organic in time and place and that the overall tone feels too close to Spielberg’s own style from that bygone era. Super 8 works only marginally as a faithful reproduction of The Beard’s work, but it falls rather short at being fully convincing in its own right. My other major beef is with the monster… an alien that bears a striking resemblance to another Neville Page design from Cloverfield and is quite reminiscent of the classic Alien Queen design (though not as gender specific). The monster sequences, after the big train effect, tend to be the least interesting part of the film, and are filmed so as to evoke that special sense of fear, awe and mystery that Spielberg’s films were so good at capturing. It’s a rather unmemorable, but complex creature design, though the effects work that gives it life is as convincing as any CG effects are these days (convincing, but not as organic as say the Rancor monster from Return of the Jedi, another classic creature this alien being strongly resembles at times). The creature must also sell a key moment at the end of the film (which won’t be revealed here), and in order to do that must convey some particularly human qualities… and while it does seem convincing, I had absolutely no empathy whatsoever for this particular alien. Lovable E.T. it’s not, but that doesn’t mean we can’t feel something toward this creation of data and pixels (as opposed to rubber and wire). Spielberg had, at one time, envisioned some rather scary aliens himself in the days when E.T. was still a developing project. His infamous Night Skies aliens (designed by Rick Baker) were to be rather malicious and nasty**. The Super 8 creature simply doesn’t rank as a particularly scary monster, nor an exciting one. Compare it to the rather simple design of the alien monsters in Joe Cornish’s Attack the Block (a hugely underrated film that had but a sliver of the production/marketing budget of Super 8) and you’d be stunned at how ineffective Page’s design is for Abrams’ film. Right there, the movie loses a huge amount of credibility (heck, Noah Emmerich’s portrayal of the stock mean ol’ Air Force Colonel is downright fearsome compared to the creature we’re all supposed to be terrified about), credibility that’s hard to buy back once the third reel completes the adventure and ties up the relationship issues that the beginning of the film set up so well.

human qualities… and while it does seem convincing, I had absolutely no empathy whatsoever for this particular alien. Lovable E.T. it’s not, but that doesn’t mean we can’t feel something toward this creation of data and pixels (as opposed to rubber and wire). Spielberg had, at one time, envisioned some rather scary aliens himself in the days when E.T. was still a developing project. His infamous Night Skies aliens (designed by Rick Baker) were to be rather malicious and nasty**. The Super 8 creature simply doesn’t rank as a particularly scary monster, nor an exciting one. Compare it to the rather simple design of the alien monsters in Joe Cornish’s Attack the Block (a hugely underrated film that had but a sliver of the production/marketing budget of Super 8) and you’d be stunned at how ineffective Page’s design is for Abrams’ film. Right there, the movie loses a huge amount of credibility (heck, Noah Emmerich’s portrayal of the stock mean ol’ Air Force Colonel is downright fearsome compared to the creature we’re all supposed to be terrified about), credibility that’s hard to buy back once the third reel completes the adventure and ties up the relationship issues that the beginning of the film set up so well.

In the final analysis, Super 8 is fun, but not entirely imaginative. It feels slap-dash (and Abrams more or less admits it was during the development process), and only as fun and exciting as your memory of Spielberg’s old backyard adventures allows. There are scenes in Abrams’ film that are lifted almost wholesale from The Beard’s early oeuvre, particularly Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Young Charles’s family homestead is just as messy/crazy as Roy  Neary’s lower-middle-class digs were… but it feels less realistically blue-collar. Perhaps that’s because Spielberg was catching an actual era on film… those were the times! That was how people were, and the Neary family seems as realistic for the mid-70s as I remember any number of families being (especially those with one too many kids and bills piling up). The electrical linesman sequence in Super 8 might have come directly from CE3K’s cutting room floor footage, and the Air Force as depicted in the film is as reasonably unscrupulous as the military brass from Spielberg’s classic alien films (determined, scary, mysterious, but very human in the end). While it would have been nice to see Abrams throw in a bit of homage here or there as added spice for film geeks (like the sprinkled references to a real king of indie cinema, George A. Romero, who gets name checked and seems to be Charles’s true cinematic inspiration, or the fact that Glynn Turman from Gremlins is cast in a similar role), filming entire scenes as Spielberg once did seems like an overly fawning move to make in Abrams own early career and leaves Super 8 standing as only a shrine to Spielberg’s talents rather than Abrams’ own.

Neary’s lower-middle-class digs were… but it feels less realistically blue-collar. Perhaps that’s because Spielberg was catching an actual era on film… those were the times! That was how people were, and the Neary family seems as realistic for the mid-70s as I remember any number of families being (especially those with one too many kids and bills piling up). The electrical linesman sequence in Super 8 might have come directly from CE3K’s cutting room floor footage, and the Air Force as depicted in the film is as reasonably unscrupulous as the military brass from Spielberg’s classic alien films (determined, scary, mysterious, but very human in the end). While it would have been nice to see Abrams throw in a bit of homage here or there as added spice for film geeks (like the sprinkled references to a real king of indie cinema, George A. Romero, who gets name checked and seems to be Charles’s true cinematic inspiration, or the fact that Glynn Turman from Gremlins is cast in a similar role), filming entire scenes as Spielberg once did seems like an overly fawning move to make in Abrams own early career and leaves Super 8 standing as only a shrine to Spielberg’s talents rather than Abrams’ own.

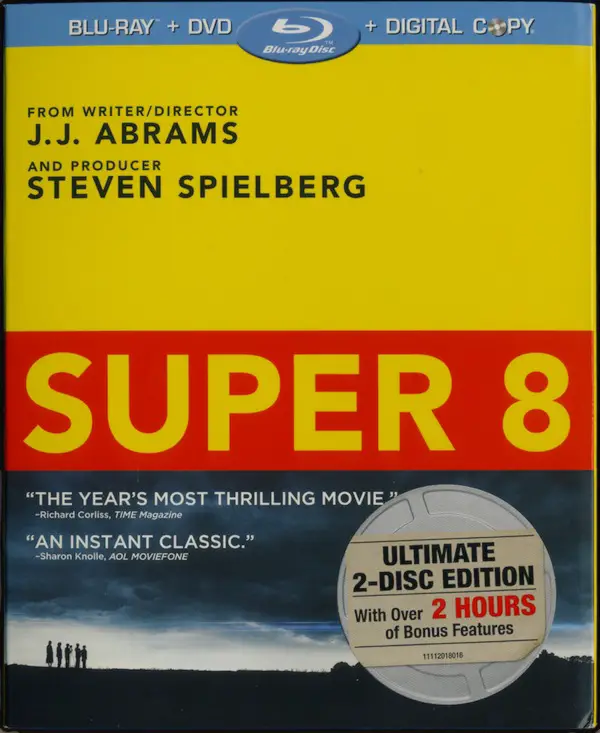

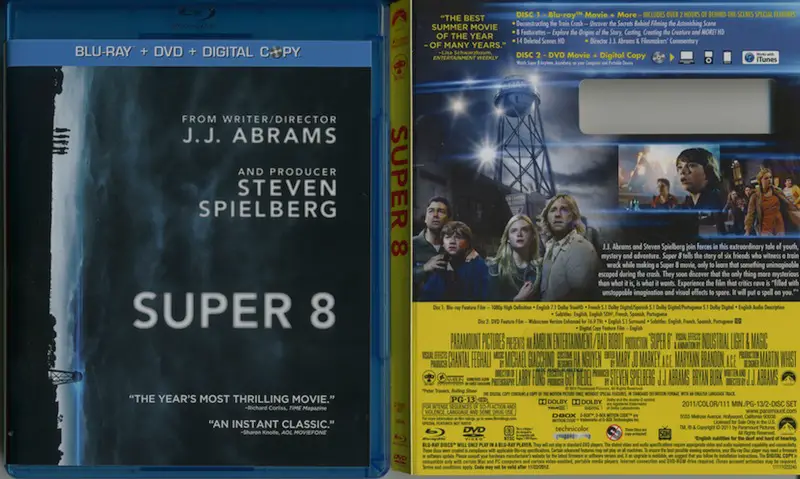

The Blu-ray is, like many big-budget movies from the major studios, an excellent release from a technical standpoint… The transfer is as it should be: a perfect representation of what was shown in theaters (perhaps even better because HD home theaters are starting to become terrific showcases for films than actual theaters nowadays). As the director’s commentary notes, the actual filming was done mostly with 35mm stock and the RED camera system (for later retakes, pick-ups, inserts) but also utilized Super-8 film, of course… the actual movie within the movie the kids are shooting is created on the genuine film stock Kodak put out in box-like cartridges (yes, you can still buy them). It all looks seamless, and the Blu-ray maintains an accurate visual quality with deep blacks that leave in the shadowy details some transfers might otherwise crush into dark mud, consistent grain balance, excellent reproduction of flesh tones (as they were in the theatrical release) and deep color reproduction with no bleeds. Overall it is a great transfer, perhaps the best of 2011 (not counting re-issues/restorations). It offers a tight and crisp picture along with a downright impressive level of sharp detail and no noticeable edge enhancement or apparent DNR (the only image softness I saw was what Larry Fong intended and captured as he switched apertures due to set lighting issues or blew out the background when changing focal lengths). Of course, like most top-notch Blu-ray releases these days it’s hard to tell how good the quality may actually be as there is so much post-production digital tinkering going on in contemporary movies before they hit the theater screen, but when compared to the the DVD disc (Disc 2 of the 2-disc package that also includes the now ubiquitous digital transfer for iTunes/Windows Media Player) and you can immediately see the difference in the level of detail, color saturation, and black levels.

Sound quality is also as it should be for a generally high-profile release from a big studio… distinct and perfect, using multi-channel effects in a way that completely envelopes you in the movie’s aural environment. LFE are accurately reproduced and will shake the house, but again they are distinct and nicely mixed without drowning out mid-range dialogue or the sharp, high-end frequencies. The Dolby lossless 7.1 TrueHD track is superb and captures the home life sequences with all the ambient nuance you’d expect from such a transfer while also delivering a sonic wallop during latter scenes when the bucolic small town is turned into a complete war-zone.

The transfer is impressive throughout, but especially during the long, child’s-eye-view, train crash sequence. From start to finish, that sequence is a marvel of wonderfully realized CG effects and brilliant aural cues (from the legendary master of sound design, Ben Burtt). Play this one back to your guests on a nice HDTV with a killer home theater audio setup and watch their eyeballs bulge and jaws drop. The sequence is superbly executed (serving crucial function as both backstory and the starting point of the kid’s adventure) and is easily the effects centerpiece of the film. It also is the highlight of the Blu-ray’s special features which offer roughly over two hours of cast interviews, filmmaker commentary, deleted scenes and an impressive stand-alone extra that dissects the the train crash sequence from soup to nuts. It’s a viewer-guided experience that offers a glimpse into the combined effort it took to successfully create the extended chain-reaction wreck, including how crucial sound was to the overall experience.

The HD features are good, but not amazing like, say, those impressive Watchmen extras from Warner Bros. (on a film that did middling business in comparison), but it’s obvious from what we get here that Super 8 probably didn’t live up to the box-office potential that Paramount had in mind for it. Nevertheless, Abrams and his coterie of filmmaking companions seem quite happy with it, and the movie’s commentary track (Disc 1) bear that out with Abrams, producer Bryan Burk and cinematographer (and accomplished magician!) Larry Fong discussing the fun they had making it, the joy of working with the kids and the fact that they got to realize their own lifelong filmmaking dreams by starting out on home movie cameras… cameras designed to capture everyday life, and backyard adventures.

The commentary is nice, but at the length of the film itself, a bit boring at times… there are no real key insights beyond the basics—the development of the film from script-to-screen and how Spielberg himself had an immediate impact on it, the gathering of talent and the cast, some of the pressures of making such a complex film, etc.—while the rest of the commentary is based more on the filmmaker’s own childhood memories experimenting with Super-8 cameras and is rounded out by an extended running joke where Abrams and gang attempt to email The Beard a real important question, but really get around to it… It’s not particularly funny, but they yammer on about it in yawn inducing fashion.

The disc also includes an extended (over an 1-1/2 hours) EPK featurette containing:

- The Dream Behind Super 8

- The Search for New Faces

- Meet Joel Courtney

- Rediscovering the Steel Town

- The Visitor Lives

- Scoring Super 8

- Do You Believe in Magic?

- The 8mm Revolution

All segments are nicely done and serve to illustrate key points in the creating the movie. A day in the life of young Joel Courtney is rather fun since he’s so new to the process of feature film acting and his excitement is palpable. When he’s not in awe at the prospect of being in a movie, he seems quite professional and would have a great future in movies should he decide to continue. “The Dream Behind Super 8” is a worthy feature as well, showcasing some of the early talent these filmmakers had with Super-8 clips from Spielberg, Abrams, Fong and even Michael Giacchino. The trip to Weirton, West Virginia (“Rediscovering Steel Town”), where most location filming took place, is probably the only EPK extra that’s ever brought a tear to my eye and is a loving look at a town that time (and the economy) kinda forgot. But, for sheer fun, the best segment focuses on Larry Fong’s predilection for prestidigitation on the set… The guy can really do some seriously mind-blowing magic tricks when he’s not indulging his director’s penchant for lens flares and deep focus action.

As for other extras… Well, Blu-ray still isn’t being used as originally intended by the studios. Either they’re lazy or just don’t give a shit about Blu because they’re now focusing on revenue sources beyond physical disc formats. Go figure… while this disc offers plenty of decent extras, none is particularly amazing or well integrated within the the feature film’s playback mode. They are isolated as bonus features, and beyond that there is a complete dearth of BD-Live functions (nothing save trailers). And, by the way… who uses D-Box? I’m glad they include for the several or so gamers that may have bought a D-Box chair when the concept was initially being sold, but it’s kind of a joke to most consumers who will never invest in it. So, for this release, we’re left with subtitles in English, English SDH, French, Spanish and Portuguese… yay. The Dolby 7.1 track is English only, if you speak French or Spanish you get a 5.1 DD track. The SD DVD (Disc 2) offers a 5.1 DD in English only (with subtitles). Here’s what the packaging breakout looks like:

So, is it worth the buy? Yeah, for the right price (definitely not the MSRP). It’s a fun movie for kids and adults alike… just not a great movie, not the movie we should have gotten from all the hype and anticipation that surrounded it as a big event film on par with Spielberg’s wunderkind output. Gen X/Y folks may get a kick out of it’s familiar 70s feel and homage to great popcorn entertainment from their own childhoods, but I don’t think it will ever withstand the test of time as Steven Spielberg’s own films have from that era. Nevertheless, as far as Blu-ray discs go… this Paramount release would make a great showcase disc to wow friends and family who haven’t yet gotten a clue as to Blu-ray’s potential (even at this mid-life stage of its cycle, Blu is still only making gradual inroads as folks cling to DVD). It is an impressive addition to a Blu-ray library on looks and sound alone, rather than content only, and Paramount should be commended for the exquisite transfer… but what will give it replay value in the long run is a great cast of kids acting for all the world like they’ve been lifelong friends before even gathering for their first take in front of a camera. If Abrams is anything at all like his idol, it is here in the direction of his young actors, and that makes Super 8 well worth watching.

* For this wonderful term that covers Spielberg’s small-scale adventures like The Goonies and Back to the Future (films where Spielberg is listed only as producer, though his directorial influence is all over them) I’m indebted to writer Janine Pourroy who coined it for an article in Cinefex Magazine. I think the term aptly describes Spielberg’s earlier feature work wherein children/families confront and cope with inexplicable or inconceivable events in mundane, suburban settings. Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Poltergeist (producer credit), and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial all fit into this category, while Jurassic Park, though far from suburbia (and a mid-career effort for The Beard), follows the same beats in terms of story and character by way of a surrogate family.

** Though the project withered in development, it eventually became the genesis for E.T., Gremlins and, to a lesser extent, Poltergeist.

Original Publish Date: Nov. 25, 2011

Image Credits/Usage: Contact Us